I don’t think I ever knew nor understood how my parents became who they were. I only remember their lives from the mid-1960s and when I try to imagine their own upbringing as children and young adults, I am at a complete loss. I can only go off half-remembered stories that they would occasionally tell me and from reading books or watching TV documentaries about life between the wars. So I am unable to put into context how they became the people who I subsequently knew.

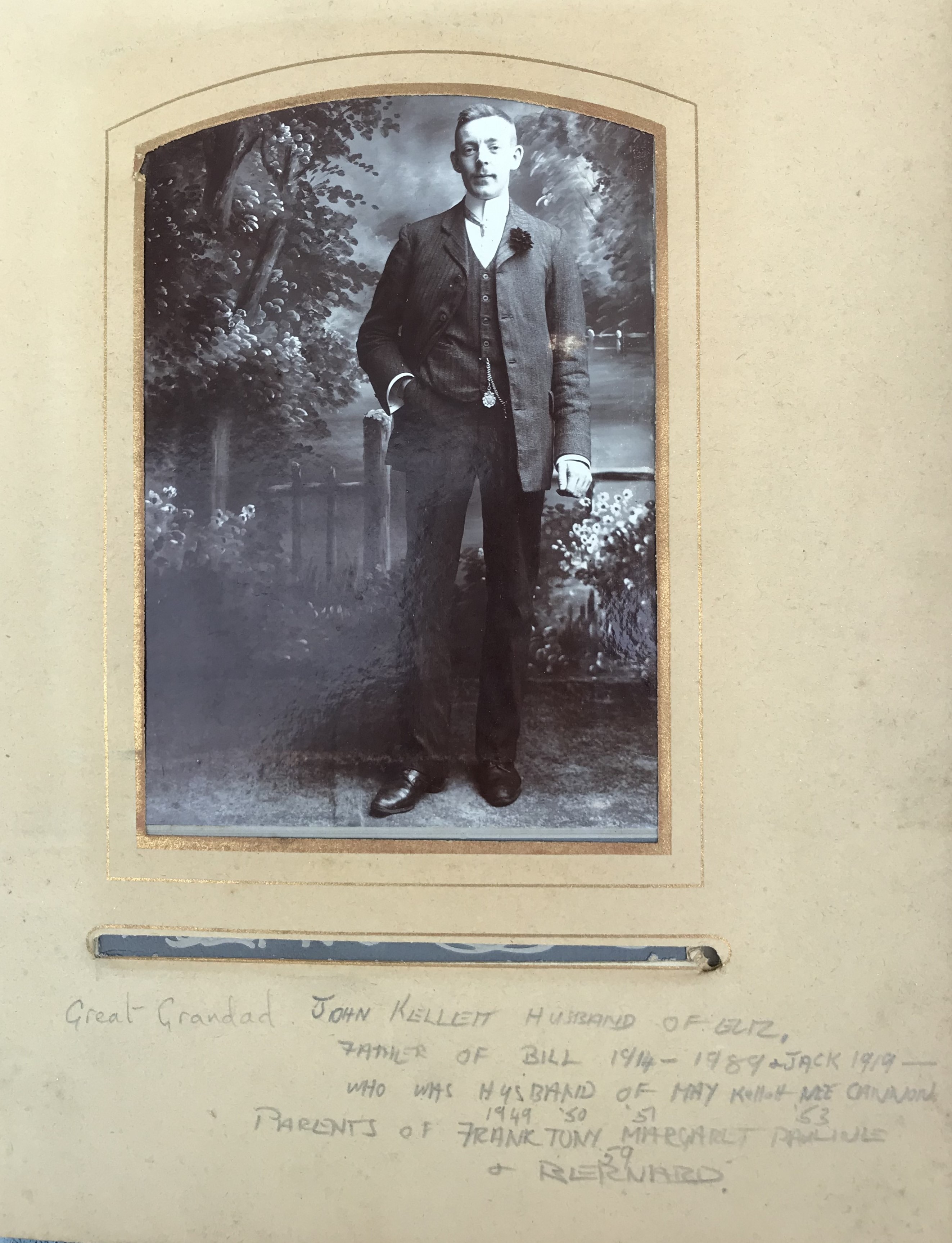

My dad was born in 1914 a few weeks before the Great War, so he remembered nothing about it. He never told me any stories about it, so I suspect that it never directly affected him nor his family. His own dad died in 1920 and so my dad barely remembered him. At that time, his mum moved back to live in the family home, Roscoe’s Farm, although I don’t know where they lived for the first few years of their married life. Losing his dad so young also meant that he only had one younger brother, Jack, which may have been unusual for a Catholic family of that era.

Dad never talked about his childhood, but I know that after he left school at 14, he started work at Disley farm which was adjacent. His eyesight was very poor from an early age, and so he never owned a driver’s licence. He maintained that he knew how to drive and told me that he’d driven tractors as a young man. Tony recalls once visiting him at work in the late 1960s (possibly taking Dad his lunch if he’d forgotten it) and seeing him driving a fork-lift truck to load a wagon, an activity which requires a good level of skill and coordination. Tony also reminded me of a story that Dad often repeated which was that whilst working on the farm he was once tossed by a bull he was handling. Only a fortuitously placed gate allowed any of us to even exist.

I’ve just re-read the previous paragraph and when I say that my dad never talked about his childhood, could it have been because I never asked him? He may have wanted to tell me stories of how he grew up, but I may never have expressed sufficient interest for him to tell me. That’s very sad, if it’s true. And perhaps it’s the underlying reason why I’m writing this account, so that if my own children realise that they know little about my own childhood, they will have some resource to fall back on even if I’m not there to ask.

Dad’s life during the years before I was born remains a mystery to me. Although he rarely spoke of this time, I get the impression that he was content with his own company with no desperate need of friends. He worked as a labourer, although my knowledge here is vague. Tony recalls that Dad talked about carting produce in the 1940s to Washington Hall in Chorley when it was an American Air Force base and removing all the waste food from there (they were Americans after all!) to take back to the farm where it would then be boiled down for swill to feed the pigs.

Towards the end of the war, Dad met Mum, and some of that detail is recorded in Mum’s diaries. She kept diaries throughout much of her life, and they are still in the family. The first one is from 1945, but then there is a gap until 1951. From that year, however, apart from eight years between 1958 and 1965, there is a written record giving a reliable account of her life. Sadly, I guess like many diaries, mundane entries are interspersed with more important ones. Many days simply record that Mum managed to get the washing dry or that she bottled 12lbs of fruit, but the more significant entries have helped me add to what Mum had already told me and to construct the next few paragraphs.

When Mum was nineteen she had a boyfriend, Bill Riley, but he had joined the Navy and was sent out to Gibraltar. While he was away, Mum still went out to dances, and in May 1945 she attended a dance at St John’s club in Whittle and she met Bill Kellett, my dad. He asked her for a dance, and while they waltzed around the room, he sang along to the music which she found very romantic. And that was the start of a relationship which would last well over 40 years. She learned that before the war, my Dad had his own dance band, but when the musicians in his own band were called up to fight, he began to play double bass and sing regularly with another band called the Frank Jackson Trio who were from Leyland and regularly played at Leyland Motors Club. Frank Jackson, incidentally, was the organist at Leyland St Mary’s church.

Mum already knew of Dad since he sang in St Chad’s church choir and she had always admired his voice when he sang any solo parts. Mum often stated that another thing that had attracted her to him was that from early summer to October, Dad always wore a rose in his buttonhole each Sunday. You rarely see men wearing buttonholes apart from at weddings now, but for Dad, it was routine.

Not long after they began courting, Mum asked Dad how old he was. His response was, “I’ve been dreading you asking me that question”. Since he was then in his 30s, twelve years older than Mum, he thought that this would scupper any chance of romance that there may have been between them. He also admitted at that time (full disclosure) that he would possibly become blind over the next decade. This was brave of him, since with all the fit and healthy young men soon returning from the war and increasing the competition he may have struggled to find a life partner. However, his honesty paid off, and Mum accepted his proposal of marriage.

His future mother-in-law didn’t approve, however, and warned Mum in blunt terms that if she went ahead with this relationship, she ‘will soon be a young widow’. The warning was ignored, however, since Mum and Dad were married on Easter Monday 1948 which in that year fell on March 29th. They were married at 9:30am, as was typical in those days, and so after the wedding breakfast, they might have had just six hours for a honeymoon, before Dad had to go back and milk the cows.

Despite her mum’s stern warning, although my mum did spend 18 years as a widow, she enjoyed over twice as long being happily married. I never doubted that my parents’ marriage was happy although Mum did spend some time struggling with what I think now may be diagnosed as depression. This was caused by external factors, mainly through caring for older relatives and navigating through the difficult teenage years of her children. Her diaries document these difficult times and in parts can be challenging to read.

Without any diaries to consult from 1948, the next bit is supposition on my part but since at this time Dad’s brother, Jack, was already married with a family, if Dad left home, the only people living at home would be Dad’s mum and his two aunts, Polly and Kate. So as a matter of convenience, Mum and Dad came back to live back at Roscoe’s Farm. Although it did hold some livestock, at only five acres, it was not viable as a farm to provide a family income and so after he was married, Dad continued to run Roscoe’s Farm part time and work full time at Disley Farm until it was sold in 1951.

An aside. I’ve only now realised that apart from the first five years, Dad had lived at Roscoe’s Farm all his life. In 1997, finding the house too big for her to maintain, Mum was looking to move out. Geraldine and I briefly considered whether we could buy it, but having a young family, and knowing what essential maintenance the house needed, we concluded that we couldn’t afford it and let it go. The house came up for sale again recently, but after all the work that had been carried out on it, it was even further out of our price range. I’m suddenly feeling quite nostalgic about the place.

After he left Disley Farm, Dad worked for some time for a haulage company called Low and Coxhead who were based in Moss Lane in Whittle-le-Woods. Their yard was by the canal in Whittle-le-Woods in the place which is now occupied by the Malthouse pub. I suspect that his job was to load and sheet up the lorries, which may not sound like a full-time job, but without any mechanical aids, I guess this would have been long and arduous work. And probably lonely. From Mum’s diaries, I can see that he often had to travel to various places on the wagons which would account for his wide knowledge of Lancashire and Cheshire. In the mid-1950s, Dad moved to another company who were based in Adlington.

From my own earliest memories, I knew that Dad worked night shifts. He started on nights in 1955, and Mum once joked that the reason I was born almost 5½ years after my sister was because my dad had just stopped working nights. I’m not sure how true this was, but it made a good tale when Mum decided that I was mature enough to understand and not be offended by it. In her lighter moments, she also related a story that the local priest had once commented that Dad working nights was an allowable form of contraceptive. He must have switched back to night shifts soon after I was born because as I was growing up, I was always aware that Dad was in bed trying to sleep whilst I was playing in the house, so I had to play very quietly. I expect that working regular night shifts would prevent much of a social life, but he never appeared to regret this, a feeling which I can understand. He did go out at the weekends though, but this was to provide the entertainment for others.

An aside. One night when Dad was playing with the dance bands, he was approached by a chap who was very short of cash, and he was asking if anyone could lend him some money. I don’t know the details, but seemingly Dad offered him money but wanted something as surety. The man was wearing an expensive snake ring and handed this over. The man never returned the cash, but Dad now owned a lovely 18ct gold ring. The ring was fashioned from a length of tapered gold about 6” long looped into a ring and formed into a mouth shape at one end with a pair of diamond chips for eyes. This ring was gifted to me on my 18th birthday, and I treasure that ring enormously, even though I rarely wear it. Mum & Dad had copies of the ring made for Frank and Tony for their 18th birthdays, but I was very fortunate to receive the original.

When I was growing up, it seemed like every Saturday night, Dad would go out early evening with his string bass and not return until well after my bedtime. He had a lovely tenor voice and he sang and played double bass for various dance bands for most of his life. He would reminisce about going to dances during the blackout carrying his bass on his back. He said that people would often bump into him because they couldn’t see properly in the dark and never expected to meet anyone carrying a string bass around. Mum’s diaries regularly have entries each weekend which said simply “Bill working”. The venues varied but were at clubs usually around Chorley and Leyland and these jobs must have been a valuable supplement to the family income.

I rarely heard Dad sing, apart from in the church choir. I have a vague memory of one time, probably at an annual church dance, when he was asked to sing a number or two. I think he must have sung ‘Edelweiss’, a ballad from the Sound of Music, because whenever I hear that song now, I think of him although I can’t recall how this made me feel at the time. The Latin hymn Panis Angelicus also reminds me of him, but I would have heard Dad singing that in church when I was in the choir.

An aside. I’ve never discovered how Dad learned about music. It wouldn’t have been taught at school, and yet he could play string instruments (he owned violins and a double bass) and he was able to read music. How did this happen? Was it simply through being in the church choir, perhaps? Or was he just self-taught? Sheet music was always available in the house when I was young, so when I went to secondary school and was formally taught music, I was conscious of being a step ahead of many others in my class because I was already quite familiar with musical notation.

One of Dad’s favourite performers was the American singer, actor and black activist Paul Robeson. He had a beautiful resonant bass voice, and his most famous part was singing Ol’ Man River from the musical ‘Showboat’. If I have an ‘inheritance track’ from Dad, it is the Pearl Fishers duet from the Bizet opera of the same name. My dad loved it, although I don’t think he ever owned a recording of it. I struggle not to cry whenever I hear it now since the music is so beautiful. I have seen the opera twice, once at the Charter Theatre in Preston in 1999, but the second time holds a special memory for me. I was in Cornwall with my family in September 2002 and we went to see an opera at the outdoor Minack Theatre in Porthcurno and by chance, a travelling company was performing The Pearl Fishers that week. It was a beautiful afternoon, rather too hot and sunny for me to be truthful, but we all thoroughly enjoyed the spectacle. Thankfully no-one noticed me sniffling during the duet, as I tried to hold back the tears while the beautiful music enveloped me and I thought about how much Dad would have enjoyed that performance.

I do own some old records of church music that were recorded in the 1950s with his cousin, Bill Snape, who was the organist at St Chad’s church. One track is of Dad singing a solo of Nessun Dorma and other tracks include the choir. The choir are a bit ropey and I’m unsure why these recordings were made but it’s lovely to hear Dad’s voice after all this time. I think one may be a 78rpm record which I don’t have the technology to play, but another is certainly a normal LP, which I can still play after a lot of messing about setting up a turntable, an amplifier and speakers. This is perhaps the time to get them professionally copied onto MP3 or some other digital format.

I don’t recall my dad having any close friends. This will sound dreadful to some people, but if, as I suspect, his character was similar to mine, this wouldn’t have bothered him in the slightest: he would have been self-contained in that regard. He had his wife and family and that would be enough. We had many visitors at our house, far more in truth than Geraldine and I had when our children were growing up. People would often call in unannounced for an hour or so on most Sundays, although these would usually be relations rather than friends. Dad never owned a car and so we rarely went out to visit anyone. I’m sure that this apparent isolation never bothered him, although I can’t say the same for Mum.

Dad’s life when I was growing up (and probably in the previous decades too) consisted of him working perhaps 50 hours per week, playing in the dance band perhaps once a week and the rest of his time would be spent in the garden. His garden was his escape from the world. Mum often helped in the garden weeding or picking the crops, but this would be during the week when Dad was working (or asleep, if he was on nights). Dad would spend every Saturday pottering around the garden on his own. He rarely asked me for help, but if I were ever to offer, he would be visibly delighted and find me a role appropriate to my age and skills. I am ashamed to say that this would have been a rare occurrence since I never enjoyed weeding, or any fine work requiring dexterity or thought. I was reasonably happy digging or weeding with a long-handled scarifier, but I didn’t like doing anything that required getting down on my knees. That’s all changed nowadays: I’m rarely happier than when I’m knelt in the garden listening to the birdsong on a warm day. Not so much in the rain or cold.

I now wonder whether Dad enjoyed being in the garden because he could spend time on his own without having to converse with anyone. When we had visitors, Mum would call him in from the garden to greet them, but this would not happen too frequently since visitors usually called on Sunday when Dad rarely did any gardening. This was nothing to do with it being a day of rest, but because he would spend most of Sunday dressed in his best clothes. We went to the 10:15 mass at church each week, setting off at about 9:45 for the ¾ mile walk. Mass would be finished soon after 11am, but then we would spend the next half an hour in choir practice before walking home. At 2:30, we’d set off again to go to Benediction which was a short service (20 minutes or so) starting at 3pm each week. So there was little time to do any gardening, apart from digging up some vegetables for tea, or maybe in the evening weeding some of the 100 or so roses he cultivated in the front garden.

Dad loved watching comedy on TV, especially people like Morecambe and Wise, Mike Yarwood, Norman Wisdom or later, the Two Ronnies. He enjoyed simple slapstick humour, and I can still hear him roaring with laughter at such TV sketches. The whole family enjoyed these shows, partly to hear Dad laughing so much. He also loved to watch the clowns at the circus, and every year we’d be taken to Blackpool to see the Tower Circus, and their resident clown, Charlie Cairoli. I never really appreciated that humour, and today I find clowns quite unpleasant characters. I have inherited Dad’s love of comedy, however, and I appreciate simple, old-fashioned humour. I especially like verbal comedy exemplified by clever gags and puns. I admire witty characters such as Lee Mack and Paul Merton. I’m also conscious that my preferred music is generally characterised by having clever lyrics that I can relate to.

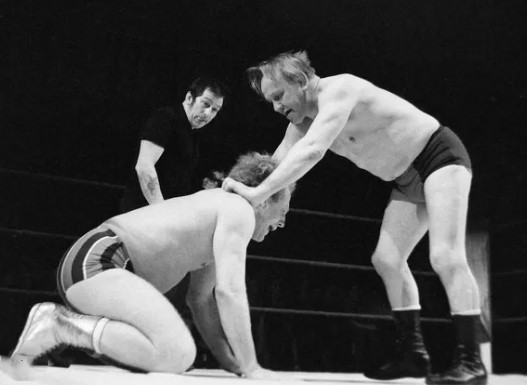

Dad loved watching wrestling which was shown on World of Sport on ITV each Saturday at about 4pm. I think it was stretching things to call this sport: it was more like a comedy event featuring overweight, middle-aged men in trunks or leotards. Dad used to come in from the garden especially to watch this every week, and the whole family would sit, enthralled by the likes of Mick McManus, Jackie Pallo, Leon Arras (which was the wrestling stage name of Brian Glover, the actor) and Big Daddy (whose real name, barely believably, was Shirley Crabtree Jr.). There was always plenty of excitement and much humour in these matches since the men clearly played to the crowd who seemed largely to be little old ladies. One of Dad’s favourite wrestlers was our namesake, a chap called Les Kellett, who didn’t seem too bothered about winning, preferring instead to entertain the crowds with his visual humour. He’d regularly pretend to by punch-drunk but then just sway out of the way when his opponent lunged for him. Whether I’d find it as funny now, I’m not sure, but I do remember the commentator, Kent Walton, giving a serious account of all the action even though most people knew that it was all carefully choreographed.

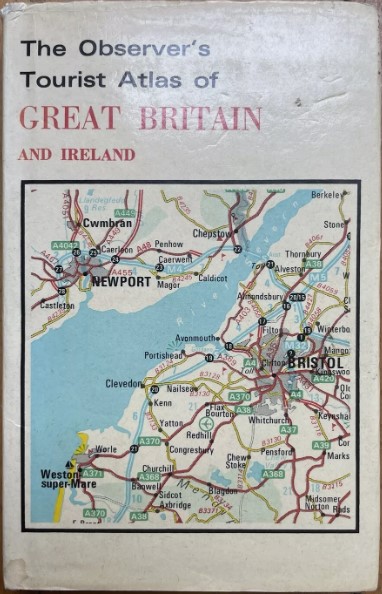

In later life Dad enjoyed going on coach trips, either day trips or after he retired, longer tours, often to Scotland. For his birthday in 1977, I bought him a tiny book called the Observer’s Tourist Atlas of Great Britain which was a pocket-sized volume containing road maps of the UK. I was delighted that he took this book with him everywhere and often had a slip of paper in it where he would write down with his tiny stub of a pencil the names of all the towns he visited. In addition, he would note all the main road numbers he travelled so that he could relay this information to me upon his return. (And yes, I was interested!). He never held a passport and never left the UK, although he did see most of the prettier parts of the country through such coach travel.

In 1973 he took me on a coach trip down to Shrewsbury Flower show, combining two of his joys, travel and gardening. He & Mum went to Southport Flower show most years, but this year, he decided to visit Shrewsbury, the home to one of his gardening heroes, Percy Thrower. Perhaps he’d suggested the trip to Mum and she’d declined, so he took me instead. I don’t remember much about the visit, but I recall being very happy being able to spend a whole day with my dad even though I didn’t appreciate gardening then. I was 14 at the time and he’d just turned 59.

I found the next part of this chapter, describing my Mum, more difficult to write, even though I have the advantage of her extensive diaries. It’s not that I didn’t know her very well, but because I never knew what she was thinking in the same way I felt I did with Dad. With my dad, I could put myself in his shoes and have a sense what his life might have been like, but that feeling isn’t there with Mum.

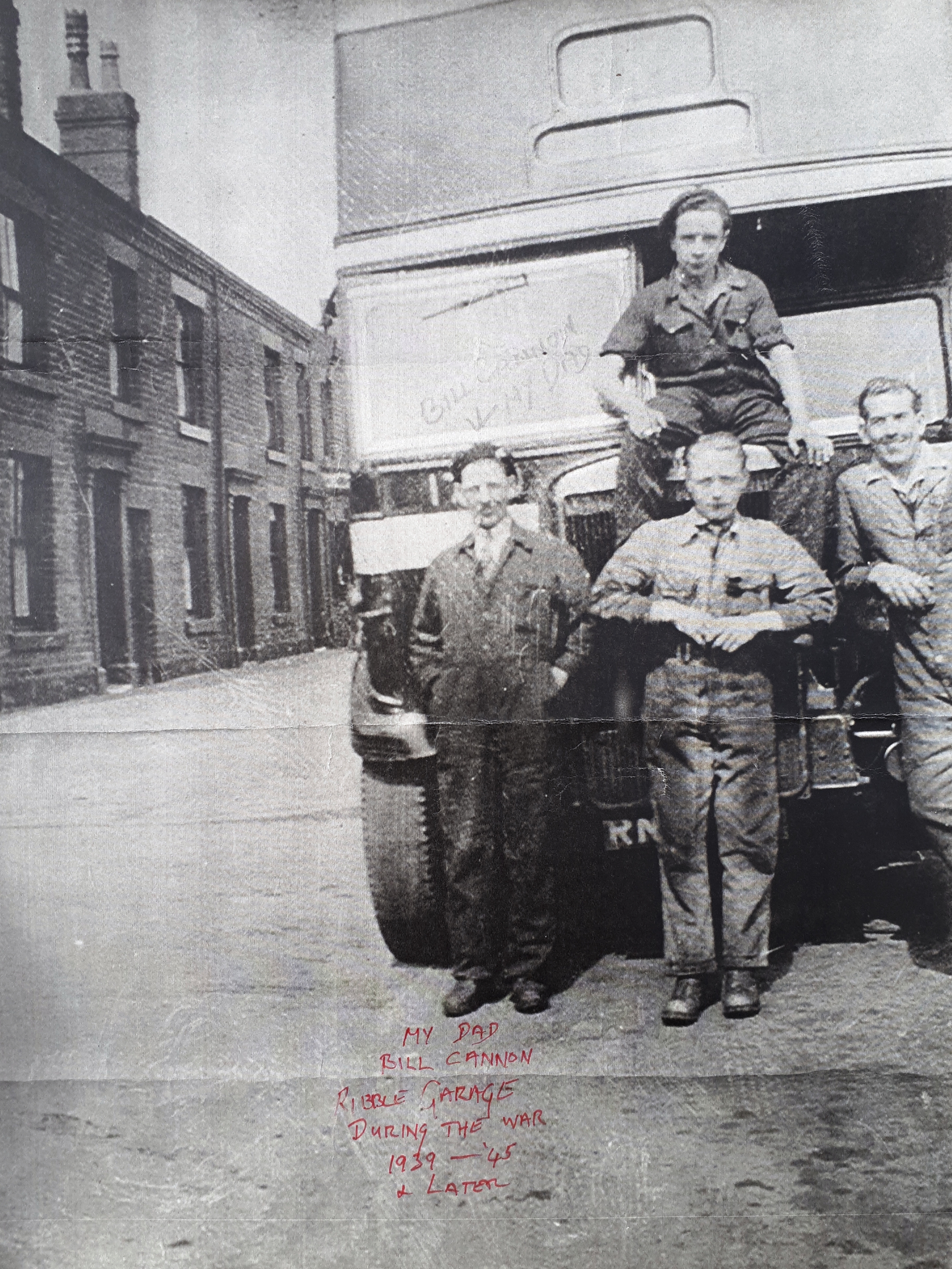

Mum was born in 1926, the second of three children, the others being boys. Her dad worked on the buses, but doing what, I don’t know. I think he worked in the Ribble bus depot on Eaves Lane in Chorley, but I don’t think he was a mechanic; perhaps he worked as a cleaner or perhaps general handyman? Of Mum’s mum, I know nothing other than that she was ‘a difficult woman’ (Mum’s words). She died of cancer in 1951 and I believe that she suffered terribly due to there being no treatment then and possibly a lack of effective pain relief.

Mum was always quite annoyed that the term ‘teenager’ wasn’t popularised until she was too old to benefit. She often lamented that she never knew that she could be awkward, moody and stroppy in her teenage years, a fact that she regretted in later life. No-one in the 1940s made any concessions to teenagers; people were considered to be either children or adults and in Mum’s case that switch occurred at age 14 when she left school. Can you be envious of your own children’s freedoms? I’m sure you can, especially when you consider Mum’s teenage years: she became a teenager on the very day war broke out in 1939 and the war only ended the day before her 19th birthday.

Mum never took part in the war although she had conditioned herself to join the Women’s Land Army when she was old enough (17½ years). This would have been in March 1944 but she never actually signed up and was never conscripted. Instead she worked in a factory which packed pills and she really enjoyed this work. The factory was Droyt Products based in Progress Mill in Chorley and they are still trading today as a manufacturer of glycerine soap. Whether they remain in the same run-down premises just off Eaves Lane, I’m not sure.

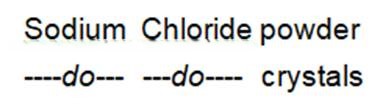

She told me a tale of her time there when she was sent out as a young girl probably to a wholesaler to collect some chemicals. She was given a hand-written list of items that would be used in making up pills. I can’t remember the name of the chemicals now, just the punch line of her story, but that doesn’t matter. The list included the term ‘do’, short for ditto, to indicate ‘the same as above’, but Mum had never come across this notation before. So at the wholesaler’s she took out the list and announced to the man behind the counter “I need half a pound of Sodium Chloride powder and quarter of a pound of do do crystals”.

The man was understandably puzzled and it was a while before he reached across for her list to see what was written down before bursting out laughing. She often related this tale to me and described her embarrassment when everyone back at the factory laughed at her for making this simple error and reminded her of it for weeks afterwards. Mum said that she was very happy doing repetitive tasks, and being quite dextrous, this would have suited her well. This is one trait that I think I may have inherited from her; I too am quite happy with repetition, and I enjoy repeating a task several times to improve my speed and accuracy.

An aside. This trait caught me out once when I was working as an apprentice at ROF Chorley. I was working alongside a maintenance engineer on a line which was filling 30mm rounds. This assembly line filling smaller shells was staffed exclusively by women and one who would have been old enough to be my mum asked if I wanted to have a go in her place and I said yes. This was a big mistake. I sat down at her place on the line and followed her instructions to do whatever task she was performing and when I became competent at it, she just walked off and left me. I felt I couldn’t stop or the process would have slowed and the line begun to back up so I just kept on working, looking over my shoulder to see if the woman was returning. The other women on the line initially laughed at my naïvety and then just ignored me and carried on working and chatting as normal. I can’t remember how long I was abandoned for – probably long enough for the woman to have a brew, or until my skilled man came back to rescue me.

Mum was a quiet person; confident when she was with friends but whenever she was near strangers or people in authority she would appear to shrink and become afraid to speak. Although in some ways my dad was similar, he would do everything he could to protect his wife and family, so any such reticence was never as apparent to me. Mum would rarely speak up for herself but instead would grumble angrily to her husband and children whenever she felt wronged. She also wrote down these thoughts in her diaries so we only became aware of them quite recently.

Mum was married at age 22 and then had babies when she was aged 23, 24, 25, 28 and 32 so her young womanhood was entirely defined by childcare and housework. It would have been a hard life, and during the 1950s she managed to cope with having four children in six years, losing her own mum and being constantly short of money. I’ve can see no evidence that living with her mother-in-law was a problem for the first few years, apart from noting that the ‘Kelletts didn’t move with the times’. She recorded that the household was very primitive and that her mother-in-law still did all her cooking on an open range fireplace which needed to be black leaded every week. It was 1955 before the road even had mains sewers and they could at last have a flush toilet (which was still outside until 1967).

The autumn of 1954 was very difficult for Mum. Her diary entries during that time describe how each of the children became ill individually or collectively over a period of about two months, and Dad was often ill as well. At the same time, they were arranging to buy Roscoe’s Farm off Dad’s mum so the finances were becoming tighter. Things gradually improved and by the time I was born in 1959, I think that many of Mum’s problems were beginning to right themselves.

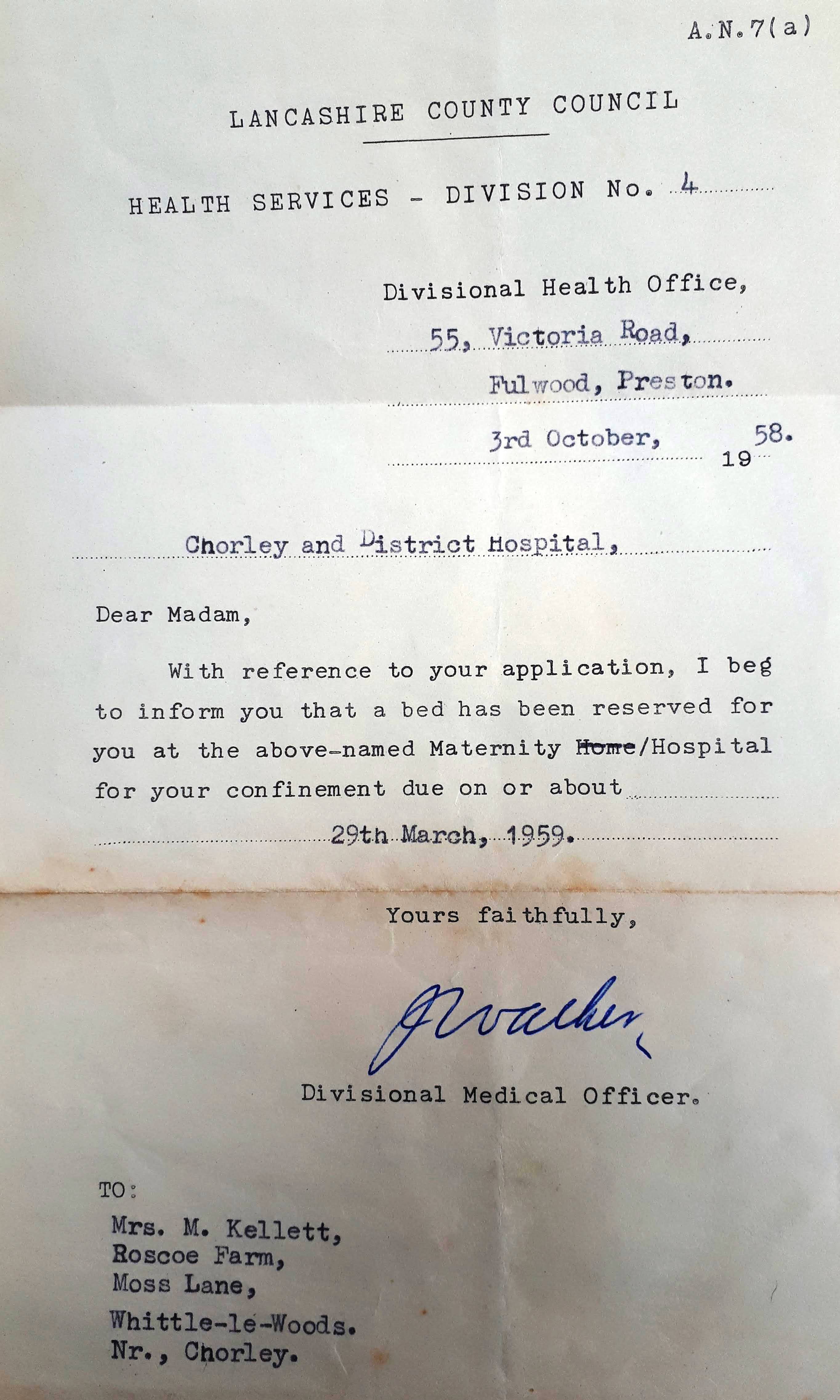

She was an experienced mum when she went into Chorley Hospital before having me. She often told me the story of a conversation she had with the staff before the birth. “What do you want this time then?” the midwife enquired. Mum replied, “I don’t care what it is as long as it’s not a boy with red hair”. And later, I popped out – a red-haired boy! “Do you want me to push him back?” quipped the midwife. Thankfully, her prejudice wasn’t so strong and I was allowed to stay, and my hair wasn’t too red and soon began to fade to more of a light ginger, a colour I always hated. I wanted black hair like my brothers.

When I arrived on the scene, my siblings were all at primary school and were probably becoming less of a burden to Mum, although they still got into scrapes like all children do. For five years I was the only baby in the house and by the time I started primary school, my siblings were at or about to start secondary school and Frank, my elder brother, had just started work. The teenage angst in that house in the mid-1960s must have been palpable and Mum had to deal with it alone. Although Dad may have been relatively enlightened in his outlook, like all men of that era, he had a clearly defined role as wage earner. It was the woman’s role to raise the children, and so I don’t think he ever got much involved in dealing with day-to-day teenage issues that my siblings would have brought home with them weekly (or perhaps daily).

In the mid-1960s things began to change. I don’t know the timings, but by the middle of the decade, although Aunt Polly had died and Aunt Kate had moved out, Mum’s dad had now come to live with us and so in a four-bedroomed house, there were four adults and five children. (Dad’s mum, Mum’s dad and my own family of seven). Mum’s diaries during 1966 and 1971 are not easy to read, and although I lived through it, I must have been protected from the worst of the trauma since I recall very little of the struggles Mum went through. She regularly wrote in the diary about how miserable she was feeling and the entries indicate that she had the sense that she was worthless. I feel that being a young mum being trapped at home all day must have made it much worse.

With very little money, Mum struggled to raise her family in a house alongside a mother-in-law who, with age, was becoming increasingly critical of her, a dad who was annoying (and getting annoyed by) the four teenage children, and a husband who, although very loving, was working nights and playing in bands at the weekend. Aunt Kate still lived nearby and was very protective of her sister and often criticized Mum about the way she ran her home, although when Kate became very ill herself in 1970, it was left to Mum to care for her until she managed to secure a place in a home. Even then, Mum spent over two years visiting her regularly which wouldn’t have been easy having to rely on buses.

From my perspective when I was growing up, Mum’s brothers, Jack and Tom, were very confident men who displayed an air of superiority whenever they were around Mum. They perhaps presented a confident appearance at all times, not just with Mum, but I have no evidence. Where did this confidence come from? Well, they both spent time in the Navy as young men so this might have had an effect. They both seemed to treat her like she was a poor relation which isn’t surprising, since that’s what she was. She was married to a labourer, with very little money and was bringing up five children. In contrast, Jack (the older brother) had a good job in the transport industry, drove a nice car and lived in a pleasant house in Blackburn. He had two children who were both ‘doing alright’ financially by the time they reached maturity. Mum’s younger brother, Tom, also had a good job and one daughter who was just a little older than me.

This simple characterisation of them may well be very unjust since both her brothers remained close to Mum throughout their lives and probably did nothing that was outwardly boastful – they simply had more material wealth. They visited us very regularly, and when Uncle Jack visited, he’d often slip a shilling or perhaps two-bob into my hand as he left. That’s not how Mum saw things, though. Often, whenever either of them left after a visit, Mum would be subdued, muttering about how they had everything and she had nothing. I’m not sure how Dad felt about this, since it was a rather unsubtle slur about his ability to provide for her.

Both uncles gave the impression of being well-off, although they probably weren’t, really – they were just better-off than we were. They both had cars which gave them considerable bragging rights over my family. Another noticeable difference was that they both drank and smoked heavily; my parents did neither (although my mum frequently tried to get my dad to smoke a pipe, which he didn’t like). Overall, even though they earned much more money, the additional disposable income was probably all spent on cars, booze and fags, so the net difference may have been minor.

Dad’s only brother (confusingly, also called Jack) was quite different again. He wasn’t rich and was much more down-to-earth. He drove a van, had a series of low-paid jobs and lived in an untidy house in Wheelton before retiring to a small semi in Whittle-le-Woods. He had four children who were always a bit wild when I was growing up. If ever I went to play with them, I would always get into trouble for something or other. I was easily led!

My mum clearly thought that her brother-in-law was beneath her, in a social sense, and I understood what she meant. The family were always a bit scruffy and down-at-heel and their house was quite untidy, unlike my house which Mum took great pride in keeping spotlessly clean. That said, I was always made very welcome and felt at home with them. I have one memory of a time when I spent a night at their house and I slept in my cousin’s bed. I couldn’t get comfy because above the mattress but beneath the sheets were all manner of small toys and books which had accumulated there. I’ve no idea why they were there, but I remember wriggling about trying to find a spot with no clutter. Uncle Jack often took me to motorcycle scramble events (his boys raced motorbikes) and occasionally to the speedway or stock car racing at Belle Vue stadium in Manchester so I have only fond memories of them.

I’m sure that Mum would initially have been attracted to Dad because he was much older than her and could look after her when she may have been feeling a bit intimidated by the world. Dad certainly wasn’t overly confident, but he always took charge whenever there were any dealings with authority. This might have changed in 1968 when Dad suffered a stroke which compromised his health. After that time, I suspect a gradual change started to occur whereby the dynamic of power began to shift. Mum was only 42 and would have been in her prime, but from that point, Dad’s health began to deteriorate, and Mum would begin to take on more responsibility. Dad was never an invalid, but he had very poor eyesight, bad feet, and in later life, angina.

When I was growing up, due to his poor health, I knew Dad would never take part in any races or strenuous activities at school sports days or fairs, unlike my peers’ dads. I’m sure that from 1968, Mum aged, if not physically, certainly mentally. For many years, whenever my parents walked anywhere, it was always at a very slow and steady pace – Dad’s pace. Mum never appeared to become frustrated by this, but just accepted it as part of growing old, even though chronologically, she was certainly not old.

An aside. Probably in the 1990s, Mum was ill and she was prescribed antibiotics. She duly took the first dose and soon afterwards came out in a painful rash. She became very ill with this and I think she may have been admitted to hospital before someone discovered that it was an allergic reaction to Penicillin! It seems that Mum had never taken Penicillin in all her life. The drug was only made widely available in 1946 so Mum would have gone through childhood without ever receiving it and clearly had never been prescribed it until she was in her 60s. I suffered from tonsillitis quite frequently as a child and was always being prescribed Penicillin, and so it seemed amazing to me that Mum had never received it.

If I could only use one descriptor of my parents it would be self-sacrifice. Everything they did was for the benefit of their children. Both parents worked extremely hard – Dad in a physically hard job which paid little with long hours. At the end of the week, he’d get washed and spruced up and head out with his enormous string bass to go and play and sing to entertain others. Mum’s role as a housewife in the 1950s with no modern conveniences would have been absolutely exhausting. I can imagine the week stretching out ahead of her with no alleviation of the chores that had to be done. Washing, drying, ironing, cooking, shopping and cleaning on top of childcare and managing it all within an insufficient household budget. They both simply continued to work hard year after year with little reprieve and after reaching retirement, my dad had just nine years when he could garden and enjoy the odd day trip and coach holidays to Scotland. When Dad died, Mum lived alone for 18 years and although she missed Dad terribly, I believe that she enjoyed those final years with her children and grandchildren giving her pleasure. She would always have her many photo albums to hand whenever we visited where she would look back on a hard life, but one well-lived.