I believe that our characters are supremely complex. As previously considered, I think that our personalities develop through a combination of genes and environment, but now I want to explore whether the context of environment may have had the greater influence on me. Who we meet, where and under what circumstances must shape our thinking over time and mould our behaviours. Many people when questioned, can often name a particularly charismatic or enthusiastic teacher whom they claim was the catalyst which set them off in a specific direction. I’ve tried to think who might have played such a role in my life but I’ve struggled to identify any individual. I don’t believe any single teacher was so influential in my upbringing that they changed the course of my life. Instead, rather than perceiving one person who gave me a big push in a certain direction, I can identify several people who I’m sure gave me a slight nudge to marginally change my life’s trajectory. Most of these people have sadly passed away but I don’t think I’ll embarrass the ones who are still with us by relating the effect they had on my nature, thinking and outlook.

The person who has perhaps had one of the biggest influences on the way the recreational aspect of my life turned out was Eddie Kelly. He was a chap who was my dad’s contemporary whom I saw at church. At age 13 or 14 I’d never really noticed him, but seemingly he’d noticed me since he began to pass me copies of Cycling magazine each week. He’d clearly seen that I was forever on my bike and although he never told me as much, he appeared to want to nurture my growing interest in cycle sport. Gradually we became, if not friends (he was 65 by then), certainly good companions. He’d chat to me about which racing cyclist was doing well, and who to watch out for. Eddie introduced me to names such as Merckx, Thévenet, De Vlaeminck and of course, Beryl Burton. These names were unknown to me then, but I listened politely and tried to respond appropriately, which would remain the pattern for many years. Although Eddie didn’t ride any longer, he was an enthusiastic follower of the sport and was keen to encourage me to have a similar interest. Possibly to his disappointment, I never did become interested in cycle racing, much preferring to ride a bike for pleasure. Even today I rarely watch cycle racing on TV nor read about it in the media.

It is entirely down to Eddie that I began time trialling: I would never have even considered it without his intervention. He had gifted me a replica Peugeot race team bike in early 1975 and with his support I rode it on my first time trial later that year. I went on to ride around 70 time trials, but I was never any good. It’s ironic that although I loved cycling and was always out on my bike, this never translated into fast times against the clock, yet although I never enjoyed running, I found that I was quite good at middle-distance events.

I took part in time trials for about 4 years and only stopped after I took a break from racing in 1980. I had recently failed my final HNC exam for my apprenticeship and had decided to re-take the final year. Sadly, by then I was outside my formal apprenticeship and so funding and time off work for college had stopped. I spent a year going three times a week to night school in Wigan at my own expense. In March, when I would normally begin to send off race entries, I delayed this activity until after I’d taken the exams in June. This removed any need to train for the races, and so my statistics for that year show that instead of cycling typically 4,000 miles, I’d dropped to just over 1,300, and over half of that distance would be commuting. After the exams (which you’ll be pleased to hear that I passed), I never really got back into competitive cycling. After a few years’ lay-off (during which time I’d bought a house and got married), I only rode a couple more time trials, with my final one being in March 1984. I never rode the Peugeot bike again. I continued cycling for pleasure but always at a slower speed, with plenty of stops to admire the views.

An aside. The Peugeot was a PR10 model, probably from the very early 1970s. When I got it, it still had almost all its original equipment – Reynolds 531 tubing, Stronglight alloy cranks with 52/45 chainrings, Simplex front and rear derailleurs, 5-speed (14-15-17-19-21) rear cassette, Mafac Racer brakes, Normandy high flange hubs with quick release axles and tubular tyres on Mavic rims. The saddle was a Brooks Racer, which I doubt was original.

The bike was four or five years old and had clearly been in a crash at some stage. The frame looked immaculate with its original paintwork, but it rode dreadfully. It pulled strongly to the left all the time, suggesting misalignment of the forks. Whatever the problem, it was tricky to ride. I could never ride ‘no-hands’, and many of my mates couldn’t ride it at all. I could hardly say to Eddie that the frame needed realigning, but neither could I afford to have it repaired (I couldn’t even afford to keep it in tubular tyres), so I just learned to live with it. It sadly ended its life at a tip, something I now regret, since someone these days would give good money for such a machine.

Without me realising it at the time, Eddie taught me about altruism and the concept of pay it forward. Expecting no return, he gave me advice, old cycling magazines, a racing bike and countless tubular tyres (which I kept puncturing). He also gave me an inter-generational friendship and introduced me to an aspect of cycling (time trials) that I enjoyed but never excelled at. He drove me to races each week took me to eat at restaurants after the events and even allowed me to drive his car as a learner driver to gain experience. Most importantly, he gave me his time.

A final thing that Eddie did for me, albeit obliquely, was to introduce me to the principle of order and formality which I have valued ever since. If there is a right way to do something, let’s do it that way. Eddie and I both joined Horwich Cycling Club in November 1973 and I quickly found that I enjoyed the administrative aspects of the club just as much as taking part in races. In 1979 I was appointed assistant Time Trial secretary and after three years as assistant I became the actual Time Trial secretary, a role I held for a further three years. It was at the cycling club that I met another person who I believe shaped my character, which was Les Wilkinson, the club secretary.

Les joined the cycling club in 1950 and was perhaps approaching sixty when I first joined. When you’re only 14, adults can be difficult to age, but Les, even then, was old-school. He didn’t actually wear plus-fours when I knew him, but I bet he’d worn them as a younger man before the war. The monthly cycling club meetings were held in the very grand Horwich Council chambers and were as formal as the room they were held in. The main room was wood-panelled throughout and had a raised bench at the front facing several rows of padded seats arranged in a semi-circle. Each row of seats was separated by a horseshoe shaped desk so each person had his or her own space to write and take notes. How the cycling club managed to gain access to this space each month, I’ve no idea, but that’s where we met.

As you might expect in such a setting, the club meetings were extremely formal, with Les taking the lead. He would welcome everyone to the meeting (there may have been 15 – 20 people present) and then proceed to read out the minutes of the previous meeting before asking, “Is everyone in agreement that these minutes represent a true and accurate record of the meeting held on nnth October?” At which point, there would be indications of agreement, after which both he and the chairman would sign a copy of the minutes before moving on to the next item on the agenda.

I was fascinated by all this formality, never having come across it before (nor since, in truth) and I really enjoyed being part of it. I was aware that most of the people present (perhaps 95% were young men) considered Les and the rest of the club committee old fuddy-duddies, but without them there would be no racing club and so none of them would be able to compete which was all they wanted to do. Looking back I am surprised that any of the young racers ever turned up, since it clearly wasn’t their scene, but this was fifty years ago and times were very different. To hear Les’ formal approach repeated each month must have had a subtle effect on me and I later found that whenever I was called upon to chair a meeting, I always fell back on the same style which I perceived as the ‘proper’ way to do things. I have since moved with the times and no longer expect that level of formality, but it remains fixed in my mind as the way things ought to be done and I think it shaped my worldview. Sometimes people say that they would love to have lived in Tudor times, or Roman or Victorian. Me, I reckon my favourite era would have been the 1950s with its typewriters, Gestetner copying machines, jackets and ties and strict behavioural norms. Oh, and cars with leather bench seats!

An aside. The chairman of Horwich Cycling Club at that time was Frank Hart who founded the club in 1934. He owned a cycle shop in Lee Lane, Horwich and his wife, Kathleen (also a cyclist), served customers in the front of the shop. The shop was narrow but went back a long way and when I used to go, I would often be invited to the rear where there would be a coal fire going and I’d stop for a chat with him and Kathleen. Frank retired in 1978 and sadly died in 1982, after which Kathleen subsequently married Les Wilkinson.

Another aside. Whilst at the club in the 1970s, one of the members was Brian Cookson whom I rarely saw, but his name was always mentioned in revered tones. I don’t believe that he had a formal role in the club, but he appeared to have many useful contacts. I lost touch with him when I left the club in 1986 but I came across his name once more when he was appointed president of the British Cycling Federation in 1997 and he was subsequently credited with turning cycle sport around. He then went on to become president of Union Cycliste Internationale and had a key role in helping to regain the sport’s reputation following numerous doping scandals.

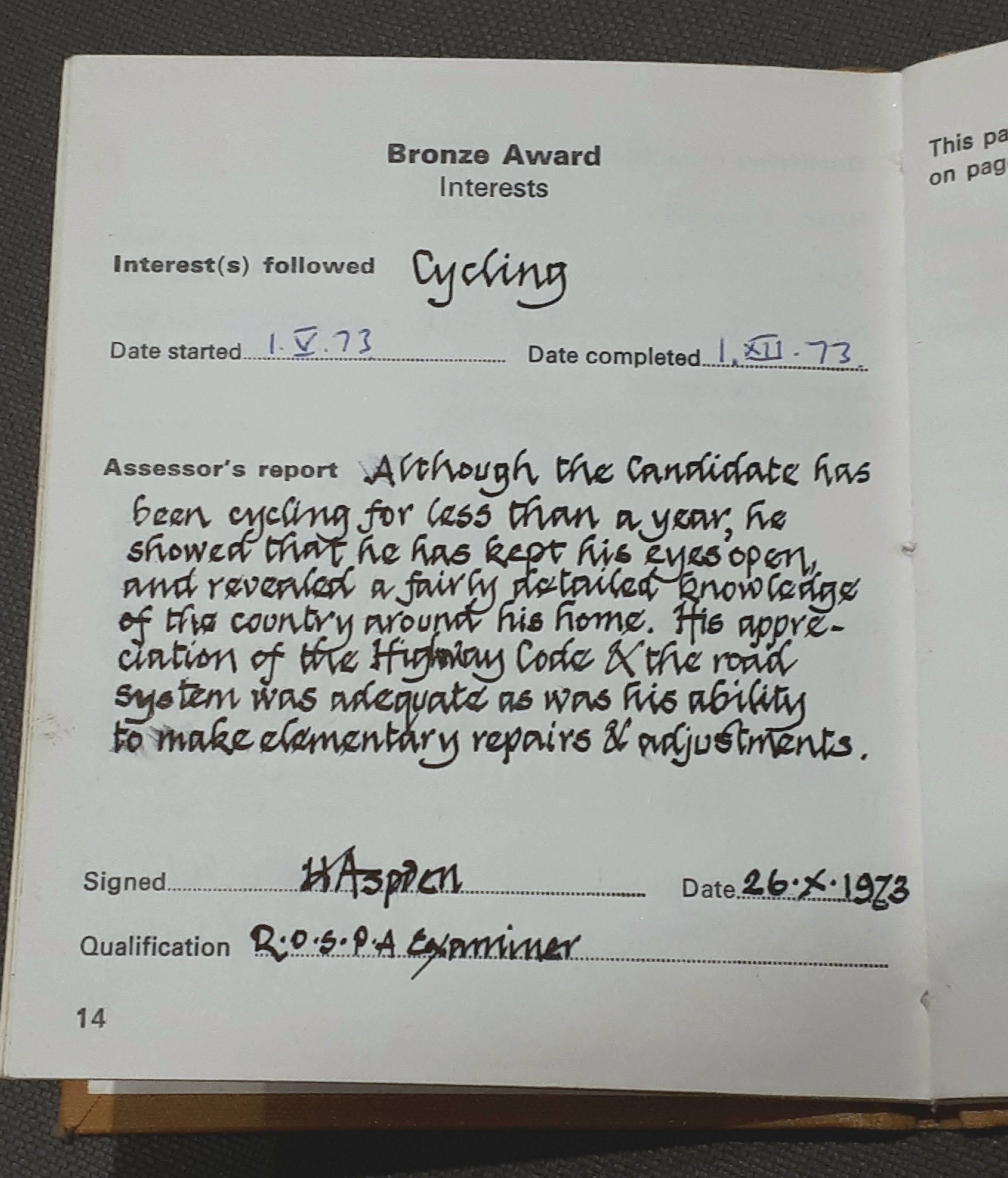

Another person I want to recognise is a chap called Harry Aspden who was a true old-fashioned cyclist that I first met in 1973. I was working through my Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme and one of the sections was to demonstrate that you had followed an interest for a number of months. I had chosen cycling, and to assess my actual interest, I had an interview with Mr Aspden who was a RoSPA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents) examiner. I was quizzed at length (it seemed) about how to maintain my bike, the Highway Code, map reading and what I had noticed whilst out cycling. The latter was rather puzzling, because in trying not to ‘lead the witness’, my inquisitor simply asked what I had seen whilst cycling out towards Croston (him having previously enquired whereabouts I’d been riding). I was stumped. Churches? Pylons? (I was still in map-reading mode). He pressed me further. “What do you see in the fields?” Cows, sheep? “No, growing in the fields”. Eventually I gave up. The answer he wanted was cabbages. He believed (and he may well have been right) that the area around Croston was well-known for growing cabbages.

In the end, it didn’t matter because he signed my booklet anyway and I went on my way. But since then, I have always been much more aware of the countryside around me, and I often try to ‘collect’ how many types of fruit and vegetables I see growing beside the road on any ride through the countryside.

I mentioned that I first met Harry in 1973, but our paths were to cross again a few years later when I was the cycling club Time Trials Secretary and he was involved with the Road Time Trials Council (the sport’s governing body). We often found ourselves at the same meetings, although he had no recollection of meeting me previously when I quizzed him about it. An ex-racing cyclist, Harry had won numerous awards and in later life he wrote many articles for the cycling press and had a regular column in the Blackburn Evening Telegraph.

I don’t even know the name of the next person to credit with influencing my life, but he ran a training course that I attended in 1984. The course was called Methods-Time Measurement (MTM) and was required for my new role as an estimator at the Royal Ordnance Factory in Blackburn. The course lasted four days spread over a month and taught the fundamentals of estimating, but more than that, it also taught me about efficiency in performing tasks. This was something that I took to heart and provided skills which I still hold dear today. Amongst many things, the main items I took away from that course were three fundamentals that I still follow:

- Always have a plan, however minor, for whatever you are about to do.

- Only ever handle items once (if possible, once you pick something up, only put it down in its final resting place).

- Always review what you’ve done to see if next time you could find a more efficient way of working.

This may sound really tedious to you and not worth doing, but once you are in the right mindset, it becomes natural. For instance, having a plan is invariably just a case of thinking through what you’re going to do before starting work which takes no time at all.

The tutor gave us an exercise at the start of the course which may seem bizarre, but I can still remember it 40 years later. He asked us to analyse how we shower in a morning; specifically, to look at how efficient we were. Bear in mind that any time showering costs money, both in the volume of water used and the cost of heating that water so any reduction in the time taken represents a direct financial saving. Any arguments that we may have put forward to say that showering is pleasurable and therefore we oughtn’t to be simply looking to do it in the shortest time were ignored. We were being taught about efficiency from a corporate perspective, and so we had to restrict ourselves to just considering the financial cost of showering. In 1984 I worked out what I thought was the most efficient process for taking a shower and I still use that method today. Of course, nothing precludes me from breaking my own rules and lingering under the hot water for longer should I wish, but my primary objective is efficiency.

The MTM system I was taught works best for repetitive tasks, so if I’m mending a puncture in a bike inner tube perhaps, my process is always the same and is efficient because I’ve repeated it so many times. I am also very specific whenever I carry out routine household tasks like ironing clothes or loading/emptying the dishwasher. There is an optimum way of performing these tasks and I believe that I’ve worked out the best way to do them (for me) and so will not deviate from the process. Logic and efficiency are key drivers of my life. This doesn’t mean that I can’t relax and go with the flow, but I admit that if I see someone working sub-optimally, I really have to bite my tongue and not intervene.

When I told my dad what I’d been learning about on the course, he said, “Oh yes, you’re studying time and motion”, but I wasn’t. MTM was all about analysing how a task ought to be done, and didn’t rely on timing someone else doing the task. During my years as an estimator, I never used a stopwatch, but I did spend hours at a desk working out the optimal way to complete a task.

Another un-named tutor offered some useful advice when I was becoming a Cub leader in 1998. I was told at a training course, “You aren’t their mum; they have mums at home. You aren’t their mate; they all have mates at school. You are their Cub Leader which is a different role altogether and a very important one.” This advice stuck with me, especially since it chimed with another learning method which I was interested in (and later went on to teach). Transactional Analysis (TA) is a theory that helps people understand and improve their relationships. It is centred on the idea that people have three ego states: Parent, Adult, and Child and each state is a system of thought, feeling, and behaviour that people can adopt when interacting with others. TA teaches us which specific ego state (persona) is most appropriate in certain situations, and I was taught that being a Cub Leader required a persona specific for dealing with eight- to ten-year-olds in semi-formal situations.

An aside. The word persona comes from the Latin word for ‘mask’ and can be defined as the personality that a person projects to others and is in contrast to their authentic self. It is true that none of us reveal ourselves as we truly are; we all wear a mask and play a role.

Lewis Wolpert, the developmental biologist, is quoted as saying that “humans are programmed to find order in chaos”. I can easily relate to that and many of my underlying characteristics stem from that fundamental belief. I don’t like anything messy or unstructured. In general, I will try to bring order to the things I encounter, but not in all cases. In my vegetable garden, for instance, the seeds must be planted in rows (primarily for ease of weeding), but in a flower bed, I appreciate that randomness is preferable. Once I get out into nature, though, I am a believer that plants should be allowed to grow where they will. Of course, with the exception of ragwort, Himalayan balsam and thistles – all of these should be eliminated entirely.

Some acquaintances have influenced me in more esoteric ways. I fondly remember Laurie Williams who was the father of a friend. I can’t claim to have known him well, but he was such a welcoming person, I was immediately drawn to him. He was a successful architect in Cardiff, but his interest out of work was in amateur radio. When I first met him in the early 1980s, I’d never come across this hobby before and I recall spending what seemed like ages in his loft talking on short-wave radio to other enthusiasts around the globe. Since this was a new completely subject to me, Laurie spent a long time explaining the technicalities and nuances involved. He turned on his radio and tried calling up random people. (I can’t remember now just how it worked, but imprinted on my memory are the repeated letters “CQ CQ CQ CQ”, which I have just found out means “Calling all stations”). I remember Laurie speaking to several people in Europe, but one man who sticks in my mind was in the USSR in a town called Kaliningrad. Neither of us knew where Kaliningrad was and we had to look it up on an atlas. (It’s on the coast just east of Poland, if you’re interested). None of this made me want to become a radio ham, but I think it was then that I became aware that it is fascinating talking to anyone who is passionate about their hobby. I have since sought out people, deliberately or subconsciously, who have interesting pastimes.

One such person was David Wilding. He was a toolmaker who acted as my skilled man teaching me my craft in the late 1970s when I was an apprentice. David was a fascinating man, with whom I could spend hours just chatting, or more often, listening. He was an engineer straight out of the Fred Dibnah mould. His house was full of bits and pieces that he’d made or adapted for specific purposes. He had a scale model railway running around his garden (I’m guessing 1:22.5 scale) which had built himself. He loved clockwork devices and had working escapement mechanisms ticking away all around the place. I think what was most likeable about David was that although he was infinitely more knowledgeable than I was, he would always ask my opinion about things. I suppose he never knew how much other people understood about any subject, so his starting assumption would be that they knew more than him and so he’d pump them for information. He’d then soak up all this knowledge and add it to what he already knew and then be able to deliver it back with a new twist. I lost contact with him many years ago when life began to get in the way, but since I first met him, I’ve been curiously drawn to the mad professor type of person. I suppose I just like enthusiastic eccentrics.

From a business perspective, a person who had a direct influence on my life over several years was Rod Hindle. Rod was perhaps 20 years my senior and he was the person who forgave me turning up late for my interview at British Aerospace in 1986 and subsequently offered me a job there. Rod was my manager (directly or indirectly) for 15 years or so and I’m pretty sure that he was responsible for my name being suggested for more senior roles in the first few years of my employment at the company. I treated him as a mentor because I liked him and trusted him to offer sound and thoughtful advice.

Rod wasn’t typical of managers in the company at that time. He was a reflective, quiet and intellectual man and not at all brash and pushy. He advised rather than instructed and always made himself available if I ever needed help. Amongst many other things, he encouraged me to join the British Junior Chamber (see chapter 10), an organisation whose members played a large part in altering my outlook. Rod was also the person who got me involved in graduate recruitment. This was one of his own roles when I first knew him, and in time, he would hand the reins over to me.

Rod, and later, Gordon, who became my boss several years afterwards, were completely different characters, but in terms of leadership, they possessed many similarities. Each had an enviable clarity of vision which took into consideration different aspects of the situation which I may have been unaware. They were both very logical thinkers and neither took decisions lightly, pondering the facts for quite a time before deciding on a course of action. Once they had alighted on a specific route, however, it was very difficult to persuade them off it. In this respect they were great leaders and I aspired, but largely failed, to be more like them.

Both Rod and Gordon were excellent at delegation, something that I never really mastered. Rod would allow me to make my own mistakes and more than once he took the time to guide me back on course if he thought I was heading down the wrong path. I think I learned more from him doing that than anything else. As a role model, he played a significant part in moulding me into the person I became. I strove to adopt his management style in that I always tried to treat people who worked for me with courtesy and respect and took time to listen to their views. I used to think that Rod and I possessed similar natures, but perhaps it is truer to say that I grew to be more like him as I matured. I first met Rod when I was 28 and I lost contact with him after he retired in the early 2000s when I was in my early 40s.

The final person I include in this category was not quite an eccentric, but someone who I had dealings with when I was treasurer of Brindle Community Hall in the early 2000s. Colin Heaton was appointed as the examiner to my accounts and we spent long evenings poring over the minutiae of the records. He was a very fastidious examiner and I wasn’t allowed to get away with anything, which was exactly as it should be. We would go through all the details until I’d managed to convince him of the whereabouts of every last penny in the accounts: we were building a new hall at the time, so the sums were substantial.

My main memory of Colin, however, is that he’d always grumble at me whenever I put a £ sign on the account sheets. He argued that since we were reading a set of accounts, we already knew that we were dealing in £s, so there was no need for the symbol. Whilst he may have been correct, my teaching at school and college was to always display the units, which I’d done. Anyway, I duly followed his request and my reports subsequently lost the £ signs. When I asked him why, his answer was simple: it saved ink. Of course, technically, he was correct, but really? Could he even measure the benefits? Any savings made certainly wouldn’t have required the use of a £ sign to quantify them.

Nonetheless, Colin pre-empted today’s focus on conserving resources; he was keen on saving miniscule amounts of ink whilst the green lobby today are keen on saving tiny quantities of electricity. When we were being chastised for leaving our TV sets on standby since it wasted electricity I thought of Colin and his ink. You or I may not notice the few watt/hours we might waste, but when a few million people all do the same, the costs to the nation mount up. However, I don’t feel noticeably wealthier from all the ink I saved.

In this chapter I set out to describe people who had influenced me over the years and caused me, in some way, to become who I am. Now having completed the section, I look back and wonder if they really did much influencing or whether they simply reinforced my own opinion of who I already was. Perhaps the real me was always there, and the mentors I’ve just described were simply allowing and encouraging me to accept and develop the traits and attributes I already possessed. Maybe I’m beginning to think that ‘nature’ may have more influence than ‘nurture’ after all.